2013

Dr Alexandra Loske traces how Victoria’s attitude to Brighton was shaped.

The first time young Victoria visited Brighton in October 1837, as a new and unmarried Queen of only 18, she was delighted by the welcome. “It was a beautiful reception and most gratifying and flattering,” she noted in her diary. “There were Triumphal Arches on all sides, and an amphitheatre was erected outside the gate of the Pavillion, filled with people.”

The Pavilion itself was another matter. “The Pavilion is a strange, odd Chinese looking thing, both inside and outside,” she wrote. “Most rooms low, and I only see a little morsel of the sea from one of my sitting-room windows, which is strange, when one considers that one is quite close to the sea.”

Her opinion did not improve, even though she chose to spend Christmas and New Year there when she visited again in 1838. That August, she recorded a conversation with Lord Melbourne, which doesn’t paint the place or the palace in a better light. “Talked of Brighton, it's [sic] being an odious place, the impossibility of sailing there, &c.; the burden the Pavilion was, and what to do with it.”

Victoria returned to Brighton three more times, in 1842, 1843 and 1845. Much had changed between the first two and the last three visits. In 1840, she married Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg and by 1842 she had given birth to the Princess Royal and Prince Albert.

In 1843, Victoria arrived from France by boat, landing at the Chain Pier, greeted by a fleet of smaller boats and crowds of onlookers on the beach and pier. A painting in the collection of Brighton Museum and Art Gallery by Richard Henry Nibbs records the event (above). But by then Victoria and Albert were already considering making Osborne House on the Isle of Wight their holiday home.

Her last visit, in February 1845, was the one Great British Railway Journeys focussed on, as the Queen and her family (by then there were four children) took the train. The railways made the journey from London to Brighton both considerably faster and, crucially, much cheaper, resulting in an unprecedented increase in visitors from all levels of society. Victoria, who had already noted how crowded Brighton was in the pre-railway age, was not amused.

On 7 February, she set off from New Cross Station in London and confided in her diary, “The railway is very well constructed & goes through tunnels & over bridges, passing through very pretty country. We only took an hour & ¼ going down! In former times it used to take us 5 hours & ½ getting down to Brighton.”

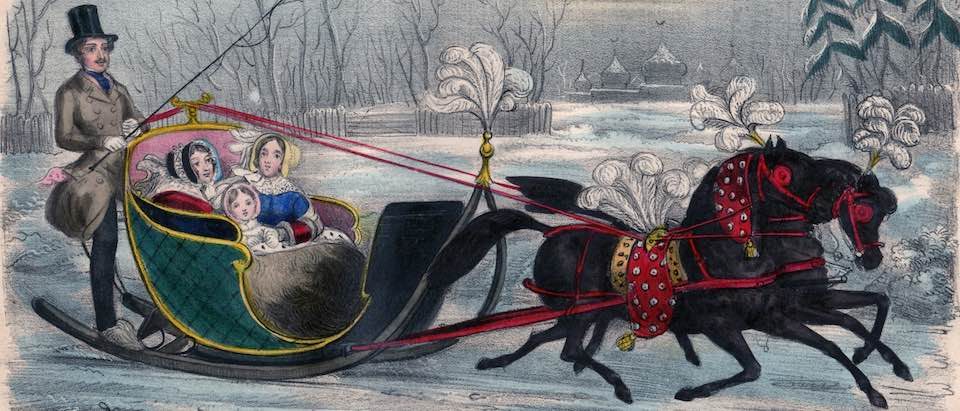

Snow fell during this visit, and on 11 and 12 February, Victoria and Albert tried out their “pretty, smart sledge”, venturing as far as Patcham and Clayton. “The horses with their handsome red harness & many bells, had a charming effect,” she gushed in her diary. “Albert drove from the seat. We went along the London road, a good way beyond Patcham, & the sledge went delightfully though the road was unfortunately very much broken up in places, but in others it was covered with snow. The bright blue sky & sunshine, together with the sound of the bells, had a very exhilarating effect.”

A print illustrating the scene (see top: image courtesy of the Society of Brighton Print Collectors) was quickly produced by the Illustrated London News. It shows a snow-capped Royal Pavilion in the background, possibly alluding to the already well-established nickname, the Kremlin of Brighton.

Sadly, Victoria and Albert also had a less pleasant experience. The papers reported on 15 February 1845 that the Queen and Consort were “exposed to much annoyance” during a walk on the Chain Pier on the Saturday morning. Although Victoria wore a veil, the royal couple was spotted and chased back to the gates of the Pavilion by some particularly rude boys, who peered under her bonnet.

The Illustrated London News lamented this behaviour, noting, “if the Queen cannot enjoy a walk without being subjected to annoyances from which the meanest of her subjects are free, it is not to be wondered that Brighton is so seldom selected as the Royal residence.”

Victoria left Brighton by train soon after, never to return. She sold the Pavilion estate to the town commissioners of Brighton in 1850 but began dismantling and removing the interior decorations and furnishings from 1846. The Department of Woods and Forests were enthusiastic in dismantling the precious interiors, leading the historian John A Erredge to write in 1851: “The ‘Woods and Forests’ had set so liberal an interpretation of the word ‘fixtures’, that in carrying off the pier-glasses, grates and marble chimney-pieces, their agents had nearly carried off the building itself.”

By September 1848, the Scientific American reported on the sorry state of the building – “Every removable article has been taken away, even to the grates, which have sold for old iron.” And by March 1850, Victoria was enjoying the Pavilion’s interior decorations in Buckingham Palace: “Walked about the new [Blore] wing, which is being furnished with many things from the Pavilion of Brighton. There is splendid china & many very fine doors, panels, &c.,…”

She had, of course, made use of the steam railways that changed Brighton so much for the worse (in her opinion) to move all the objects from Brighton to London.

However, in the 1860s she gracefully returned many important items, including the Banqueting Room chandeliers and other large chandeliers from the Music Room.

It is a process of return that continues to this day. The Pavilion may no longer be a royal residence but it is, once again, home to many items from the Royal Collection. These days, they usually arrive by road.