Twentieth Century Brighton and Hove

For Brighton, the 20th century was a period of stasis and decline, marked by extravagant plans and lost opportunities. The town’s constricted situation between the Downs and the sea offered few possibilities for growth, which meant that population increases had to be accommodated either by upping densities or encroaching onto green-field sites. Politicians and planners embarked with utopian zeal on projects that often created more problems than they solved.

The inter-war years

Between the Wars, slum clearance programmes decanted people to remote low-density estates like Moulsecoomb or Whitehawk, cutting them off from services and employment while, after the Second World War, large swathes of Victorian housing were demolished to make way for unloved blocks of high-rise flats.

Herbert Carden, whose foresight secured large areas of the Downs for the town and earned him the title Father of Modern Brighton, dreamed of demolishing the Regency seafront to make way for modern apartment blocks such as Embassy Court, while the planners Wilson and Womersley plotted to turn a large part of the North Laine into a massive road system. It was to counter such acts of vandalism that the Regency Society was founded in 1945 by Anthony Dale.

A centre of education

During the 1960s, Brighton became a centre for education and learning. A new Sussex University was built at the foot of the Downs to a master-plan by Basil Spence. This proposed a picturesque matrix of brick pavilions arranged along a spine of courtyards and lawns and has coped admirably with 40 years of growth and change.

At the same time, a number of institutions were amalgamated to create Brighton Polytechnic, later the University of Brighton. This spreads across three sites and includes the admirable Art College building from the 1960s by Percy Billington and an elegant library at Moulsecoomb by Long and Kentish.

Unexploited opportunities

But Brighton has singularly failed to exploit its brown-field opportunities. The abandoned Hove Gas Works could have produced a new city quarter of distinction – but all that transpired was a horrid supermarket in a vast car-park. The Station Goods Yard could have incorporated a new transport hub with shops and offices, high-density apartments and public spaces of real quality but it produced another horrid supermarket buried beneath buildings of mind-boggling banality.

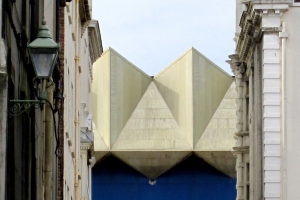

The one exception was the Jubilee site where, after 30 years of bureaucratic procrastination, Brighton finally gained a new library, designed by LCD Architects with Bennets Associates, and the surrounding North Laine enjoyed a new lease of life with its rich mix of homes, shops and small businesses.

During the 1960s, new breakwaters were built in the east to enclose a vast 70-acre marina but the project failed to fire imaginations and a large area was concreted over to make way for yet another horrid supermarket in a sea of parked cars. The future of this white elephant remains uncertain.

Buildings of note

Many of Brighton’s 20th century buildings were either, like the Kingswest complex and the Brighton Centre, truly bad or, like the Thistle Hotel, the revamped Churchill Square Shopping Centre and Boots Department Store, had been worn down to mind-numbing mediocrity by the stultifying planning control system.

Examples of good urban design from the last century are hard to find and the relatively short list of buildings of note includes the modest Allied Irish Bank by John Denman, quirky Prince’s House by H.S. Goodhart-Rendell, the streamlined Saltdean Lido by R.W.H. Jones, the poorly maintained Hove Town Hall by Wells-Thorpe & Suppel, Amex House by GMW, the Van Alen Building by PRC Fewster and the flats in Connaught Road by RH Partnership.

David Robson