The Regency Society has submitted the following comment about the latest proposals for the redevelopemnt of the Kemp Town gasworks site to Brighton and Hove City Council planning department.

BH2021/04167 Brighton Gasworks

The Regency Society of Brighton and Hove wishes to record its objection to the proposed development on the site of the former Brighton Gasworks.

The Society supports, in principle, the proposal to develop what is a derelict, polluted, brownfield site in an important location. However, it shares the concerns expressed by other responders about the risks arising from the process of remediation both during and after construction.

We also support, in principle, the developer’s stated aim to create a mixed community with a substantial number of much-needed homes.

We also welcome the attempt to create pedestrian links across the site and to connect the sea-front to Sheepcote Valley and the South Downs National Park. In this regard we regret the Council’s decision not to release the strips of land along the site’s northern and southern boundaries.

The present planning application dates from November 2023 and is the third to have been submitted by St Williams Homes (a subsiduary of the Berkeley Group). It offers a few changes to earlier submissions: the total number of dwellings has been reduced by 12 per cent; the height of one of the taller blocks has been lowered from 12 to 10 storeys; brick colours have been changed; the block in the northeast corner has been reconfigured to resemble a circular gas-holder. However, none of these changes really address the criticisms of the previous submission made by an overwhelming number of responders, including the Regency Society; nor do they mitigate what were considered to be its major flaws.

Perhaps the most significant change and one to be most welcomed, was the insertion of second staircases in ten of the blocks to meet post-Grenfell concerns about fire-escape

The Regency Society’s objections can be summarised under the following headings:

Response to the site and its location

The site is located at the eastern end of the Brighton seafront and forms an integral part of this unique heritage townscape. The applicant pays lip-service to Brighton’s heritage assets but the scale, urban form and architectural expression of their current proposal fail to take them into account: the buildings are too tall, too bulky, too crammed together; they are too much of a hotch-potch and lack any formal structuring or legibility. More specifically, they fail to respond to the scale and character of Regency Kemp Town (Arundel Terrace and Lewes Crescent) or to the clean modern lines of neighbouring Marine Gate. The applicant argues that the development does not impinge directly on distant views of the site, but this does not alter the fact that it occupies a key position in the overall composition of the seafront.

The scope of the development: density, mix, tenure

The site has an area of 2.02 hectares (c.110m x 200m). The proposed development comprises a total of 12 blocks varying in height from 3 to 12 storeys and containing 495 dwellings, giving a density of 245 dwellings per hectare (c.790 theoretical bedspaces per hectare), and a FAR (floor-area-ratio) of c.1.8:1. Such densities are high and, whilst they are comparable with other recent developments in the city, we believe them to be higher than the site can comfortably sustain. A target total of around 400 dwellings would be more acceptable. We also believe that the omission of the 14 row houses would have a marked beneficial effect on the overall footprint and would relieve the sense of congestion.

The applicant promises to create a ‘vibrant mixed community’ and we applaud their proposal to accommodate a variety of non-housing uses in the development. However, 84 per cent of the proposed dwellings have only one or two bedrooms and only 16 per cent can be described as being suitable for families with children. This sort of mix is being echoed in new developments across the city and will contribute to a serious demographic imbalance in the future.

The applicant states laudably that 40 per cent of the dwellings will be available for affordable rent, though this is only a target and it is unclear how it will be achieved.

We are also concerned that dwellings will be available on a 95-year lease and that the developer will retain the freehold and have full control over annual charges. This form of tenure has come in for much recent criticism.

Access and car parking

The scheme provides 179 car spaces (one for every 2.8 dwellings) and accommodates 629 bicycles. Residents will have to pay for parking spaces (quite substantially, if other recent schemes are anything to go by). It seems likely that many will elect to park on surrounding streets, thus exacerbating existing parking problems in the area.

The entrances to the various blocks are scattered around the site and it’s not clear how visitors, or indeed residents, will approach them. Where will visitors park? How will taxis or ambulances access the development? If one takes the example of Block 12 in the southeast corner, one wonders: how will disabled people access it, how will removal vans, delivery vans or ambulances service it?

The parking is located within two podia, one under the northern part of the site and one under the western part of the site. These are chaotically planned. The resultant entry sequences are also bizarre—particularly the entrances to Blocks B & C, which are via long, narrow windowless corridors. In similar fashion the town houses are connected to the parking basement by a long nightmarish corridor. None of this complies with generally accepted design and planning standards.

Building form

Whilst the developer pays service to heritage and what they call ‘social memory’, they fail to take on board the main characteristics of Brighton’s heritage seafront: its marine squares (a unique Brighton feature that can be seen from Adelaide Crescent in the west to Marine Gate in the east), its use of order and symmetry, and its consistent scale.

The 12 blocks are arranged in three ‘strings’ that run from north to south down the site and are separated by narrow corridors of space. This arrangement does not fit comfortably within the site width and results in narrow spaces between blocks (as little as c.16 meters) that will lead to problems of over-looking, noise and lack of privacy.

There is no formal structuring and the blocks all have different shapes, heights and sizes (and employ different materials and colours). It is as if a child had scattered toy bricks across the site.

The most incongruous element is the circular block next to the circus that has been configured, bizarrely, to mimic a green gasometer (with disastrous consequences for the planning of the flats that it contains).

The open space in the northeastern corner of the site is described as a circus but it is formed arbitrarily by the irregular ends of four adjacent blocks and doesn’t exhibit any clear geometric form.

The 14 town-houses that line the west of the site and face the back of Boundary Road seem to have been an afterthought and turn their backs on the rest of the scheme. They occupy 10 times as much site area per unit as their neighbours and thus have a disproportionate impact on shared open space provision. One wonders why 14 families are invited to live in spacious three-storey houses while their 481 neighbours are consigned to live in stacks of small flats. Paradoxically, they are the best-designed element on the site and their very existence seems to beg the question: why couldn’t the whole scheme have been conceived on a similar scale and to a similar quality with low and medium rise flats arranged around courts and mews.

The applicant provides a series of simulated and carefully choreographed distant views of the scheme (‘Heritage Townscape’) in a vain attempt to demonstrate that it will be almost invisible from any angle. However, they seem reluctant to provide explicit close-ups of the scheme. One rendering from the north reveals it to be a monumental cluster of bulky brick towers, a mini-Manhattan. Another from the southwest shows the ends of three southernmost blocks in relation to neighbouring Marine Gate. That image implies that the two developments, which occupy the same width of frontage, will be of comparable scale and bulk, but the three blocks are each considerably wider than the two projecting wings of Marine Gate and are three floors higher. When viewed from the A259 the development will appear like a huge cliff, almost twice the height of Arundel Terrace.

Climate and environment

The blocks are arranged in three parallel north-south lines with narrow chasms of space between them. As the site faces the sea these are likely to act as wind tunnels. The applicant tries to assuage such concerns by using data gathered at Shoreham Airport, which lies on a flat inland site about 15 km away to the east! These chasms will be in shadow for much of the day and many flats will receive only short periods of direct sunlight.

The blocks are designed to occupy space rather than to create space. Their linear layout breaks up the open space, much of which is contained within the chasms between them. The only substantial amenity space is found within the ‘circus’ at the northeast corner of the site. As a result, the overall provision of useable amenity open space for the projected population of 1,600 people is less than adequate.

Materials and details

Like a number of other new developments across the city, this scheme will be clad in prefabricated brick panels and, following the current trend, different colours of brick will be used in in different parts of the scheme. The choice of red brick in the northwest corner is claimed to invoke the ‘social memory’ of an industrial past (!), while the faux gasometer will be clad in green brick. The southern part of the scheme will be in a fair-faced brick to connect it visually to Marine Gate.

In fact, the whole scheme would benefit greatly from the use of a single light-coloured brick. This would produce consistency and would help to reflect light into the shadowy chasms between the blocks.

In conclusion

We wish to emphasise that the Regency Society fully supports the redevelopment of this derelict site to provide much needed housing. However, the present proposal fails to achieve the developer’s own stated aims in terms of its planning (eg, its massing, height, spatiality, circulation, legibility, etc), its architectural design (eg, scale, proportions, use of materials, etc) and its environment (eg, open space provision, microclimate, etc) and it does not lend itself to improvement by tinkering. We believe that a complete rethink is necessary.

Our own studies suggest that a total of about 400 dwellings (ie, c.200 dwellings per hectare) could be achieved using continuous blocks of not more than six storeys in height around a series of pleasantly-scaled squares. This would be in keeping with the prevailing character of the Brighton seafront. It would also avoid wind-tunnelling and benefit the microclimate. Such a configuration would result in a building footprint of about 6,000 sq.m. (27 per cent of the site) and a floor-area-ratio of about 1.6. This would support generous areas of shared communal open-space and would enable the integration of other categories of building use (a nursery, a pub, social and health related buildings, workspaces, etc). It would also include a more diverse mix of dwelling sizes (including a greater proportion of family-sized dwellings) and a variety of types of tenure.

The Regency Society of Brighton and Hove

1 March 2024

Our previous posts about the gasworks:

Brighton gasworks site: putting the heat on

Brighton gasworks site—an opportunity about to be missed?

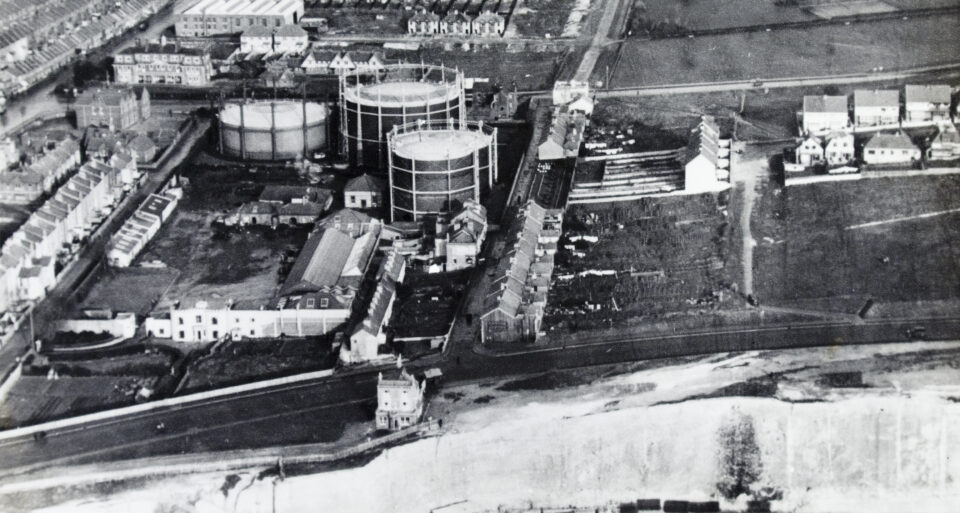

Image: The gasworks site in 1933 [RS James Gray Collection]