Victorian Brighton and Hove

Queen Victoria turned her back on Brighton and, having stripped her uncle’s pleasure palace of its furnishings, sold its empty shell to the town (read more here on why Victoria sold the Pavilion) . Thus were the bright lights of Regency Brighton extinguished. But the arrival of the railway in 1841 gave the town a new lease of life both as a London commuter dormitory and a popular destination for day-trippers.

The station, perched at the head of Queen’s Road, was built in dainty Italianate style by David Mocatta, while behind it the magnificent curving train shed, added by Wallis in 1882, proclaimed the glories of the age of steam.

Brighton continued to grow and new developments, such as those around Queen’s Park and on the Stanford Estate, sprang up on its outskirts. Here the palatial monumentality of the Regency gave way to polite rows of suburban villas, where red brick replaced white stucco and classical parapets gave way to pitched tile roofs.

A place of prayer…

As it grew, the burgeoning population demanded new places of worship of every conceivable denomination and the town was soon studded with a plethora of churches.

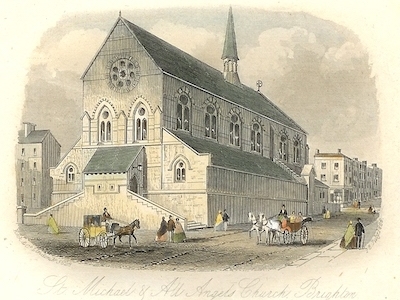

These included examples from some of most admired architects of the Victorian age, such as the exquisite double church of St Michael and All Angels in Montpelier, which was built in two stages by GF Bodley and William Burges and the cathedral-scaled church of All Saints in Hove, designed in Late English Gothic style by JL Pearson but denied its great projected spire.

Among other notable examples are Edmund Scott’s soaring Anglo-Catholic barn of St Bartholomew’s, with the highest nave in Britain, and the diminutive but delightful working class Church of the Annunciation by Dancy and Scott in Washington Street

.…and amusement

While Brightonians prayed, the trippers played and no fewer than three piers were erected for their delectation.The first of these, the Chain Pier, was built in 1823 by Captain Samuel Brown and served both as a promenade and a cross-Channel ferry terminal. Its line of pylons and connecting suspension bridges survived until 1896, when they were swept away in a storm.

The West Pier began life in the mid-1860s with a design by Eugenius Birch and was continually extended and refined until, during its heyday between the World Wars, it boasted a concert hall and a theatre. After the Second World War, it fell into disrepair and today, after fire and storm damage, its skeleton survives as a pathetic monument to public indifference.

The Palace Pier was built at the end of the 19th century to replace the Chain Pier and, in its prime, was regarded as the queen of piers by connoisseurs. It, too, suffered from neglect and storm damage but has been resurrected as a marine funfair and counts amongst Britain’s top ten tourist attractions.

Lasting monuments

During the 1890s, the cliffs to the east of the Palace Pier were developed as a monumental walled esplanade with raised terraces and elegant wrought iron arcades, all designed in a mock oriental style inspired by the Royal Pavilion. A mile-long strip of tarmac –Madeira Drive – was laid to serve as a motor racing track and now provides a theatrical backdrop to the ritual marathons, bike rides and antique car rallies that terminate there.

Perhaps Victorian Brighton’s most poignant monument is the Clock Tower, which was erected in 1887 to mark the Queen’s Golden Jubilee. This bizarre municipal phallus combined beauty and utility with typical Victorian zeal: it carried royal portraits within the four porticos that formed its base and served as both a clock and a signpost. Above its copper dome, a brass ball on a spindle was raised hydraulically and fell on the hour in response to an electrical impulse from Greenwich, while beneath its base there lurked a public lavatory.

David Robson

Images show the West Pier in 1870 (from the James Gray Photographic Archive) above, Brighton Station and the Church of Saint Michael and All Angels (Society of Brighton Print Collectors (middle)